When the Israelites strike camp at the end of almost a year at Mount Sinai1, we discover that a Midianite named Chovav has been camping with them. This week’s Torah portion, Beha-alotkha (“When you bring up”), says:

And Moses said to Chovav, the son of Reueil the Midianite, the father-in-law of Moses: “We are journeying to the place of which God said: I will give it to you. Go with us, and we will do good for you, because God has spoken of [doing] good for Israel.” (Numbers/Bemidbar 10:29)

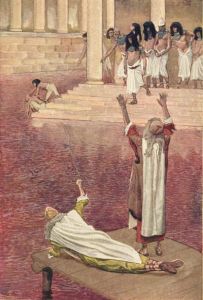

19th century

Chovav (חֺבָב) = One who loves. (From the verb choveiv (חֺבֵב) = loving.)

Reu-eil (רְעוּאֵל) = Friend of God. Rei-eh (רֵעֶה) = friend + Eil (אֵל) = God.

The syntax is ambiguous in the original Hebrew, as it is in the English translation. Is Moses’ father-in-law Chovav or Reu-eil?

The name “Chovav” appears only in one other place in the Hebrew Bible:

And Chever the Kenite had separated from the Kenites, from the descendants of Chovav, the father-in-law of Moses, and he pitched his tent as far as the great tree in Tzaananim… (Judges 4:11)

This verse clearly identifies Chovav as Moses’ father-in-law. Yet when Moses gets married in the book of Exodus/Shemot, his father-in-law seems to be Reu-eil.

Bible Moralisee, 13th century

A priest of Midian had seven daughters, and they came [to the well] and drew and filled the watering-troughs to water their father’s flock. Then the shepherds came and drove them away. And Moses stood up and saved them and watered their flock. And they came back to Reueil, their father … (Exodus/Shemot 2:16-18)

Medieval commentators and modern scholars have generated many explanations for this discrepancy.2 I believe the difference between “Reu-eil” in Exodus and “son of Reu-eil” in Numbers is a scribal error.

Both early commentators and modern scholars identify Chovav as another name for Yitro, who is called Moses’ father-in-law ten times in the book of Exodus. But if Chovav is Moses’ father-in-law, what motivates Moses to invite him to journey with the Israelites to Canaan?

Moses meets his future father-in-law when he is a young man fleeing Egypt. He stops to rest by a well in Midian territory, and comes to the aid of the seven daughters of the priest of Midian called Reu-eil. The young women tell their father what happened, and he invites Moses to dinner.

And Moses agreed to stay with the man, and he gave his daughter Tzipporah to Moses. (Exodus/

Shemot 2:21)

The purpose of the marriage seems to be to tie Moses to the family as the priest’s son-in-law. Moses shepherds for him, and gives him two grandsons. The Midianite priest apparently has no sons of his own, since they do not help with the flock.

In the next story in the book of Exodus, Moses’ father-in-law is named Yitro.

And Moses was tending the flock of Yitro, his father-in-law, the priest of Midian, and he guided the flock behind the wilderness and came to the mountain of God… (Exodus 3:1)

Yitro (יִתְרוֹ) = his yeter (יֶתֶר) = remainder, surplus. (Yitro is usually translated in English as Jethro.)

Moses has a long conversation with God at the burning bush, then asks his father-in-law for permission to go back to Egypt to see how his relatives are doing there. Yitro wisely tells him to “go in peace”.3 Moses takes his wife and children, then sends them back to Yitro before he reaches Egypt. (See my post Yitro: Degrees of Separation.)

After the exodus from Egypt, as soon as Moses and the Israelites arrive at Mount Sinai, Yitro stages a family reunion.

And Yitro, the father-in-law of Moses …said to Moses: “I, your father-in-law Yitro, am coming to you, and your wife and her two sons with her.” And Moses went to meet his father-in-law, and he bowed down and he kissed him, and each man asked about his fellow’s well-being, and they entered the tent. (18:5-7)

Figures de la Bible,1728

Moses completely ignores his wife and children, but he welcomes his father-in-law. Yitro says the God of Israel is the greatest of all gods, and burns an animal offering for God.4 The next morning, Yitro tells Moses how to delegate his workload and set up a judicial system for the Israelites.

Then Moses sent off his father-in-law, and he went away to his [own] land. (Exodus 18:27)

Moses and Yitro part on good terms, but Moses does not press his father-in-law to stay. Yitro leaves Moses’s wife and sons behind.

Over the next eleven months at Mount Sinai, Moses receives the Ten Commandments (twice) as well as many more laws. He has people killed for worshiping the Golden Calf, and he supervises the creation of the portable tent-sanctuary and the holy items in it.

Finally, in this week’s Torah portion, everything is organized for the journey to the border of Canaan. Then Moses suddenly asks Chovav to come with them. Apparently his father-in-law returned to Mount Sinai for another visit; it was not a long journey from his home.

He [Chovav] said to him: “I will not go, because I would go to my land, to my kindred.”(Numbers 10:30)

Then he [Moses] said: “Please do not forsake us, because you know how we camp in the wilderness, and you can be eyes for us. And if you go with us, then by that goodness with which God does for us, we will be good to you.” (Numbers 10:31-32)

Moses gives Chovav two reasons to travel with the Israelites: to help them navigate the wilderness, and to receive a share of the land that God promised to give them in Canaan.

What kind of help do the Israelites need? “You can be eyes for us” might be a request for Chovav to scout ahead for the best routes and camping places. But then the Torah says the ark itself is their scout.

And they set out from the mountain of God on a journey of three days, and the ark of the covenant of God set out in front of them on a journey of three days to scout out a resting place for them. And the cloud of God was over them by day, when they set out from the camp. (Numbers 10:33-34)

Earlier in this week’s Torah portion, we get a preview of the Israelites’ departure.

…the cloud was taken up from over the Dwelling Place of the testimony, so the Israelites set out for their journeys away from the wilderness of Sinai. And the cloud stopped in the wilderness of Paran. (Numbers 10:11-12)

This cloud hovers over the Tent of Meeting when the ark is in residence.5 Now we learn that when the Israelites travel, the cloud travels with them. It may even lead them, as God’s pillar of cloud and fire did when they traveled from Egypt to Mount Sinai.

Whether the cloud or the ark is doing the scouting, the Israelites do not seem to need Chovav as a guide. Rashi6 proposed an alternate meaning of “you know how we camp in the wilderness, and you can be eyes for us”. If anything occurs that Moses and the elders do not understand, Chovav could enlighten them. In that case, perhaps Moses begs his father-in-law to go with him because he remembers how the man enlightened him about delegating judicial authority. Since then, the incident of the Golden Calf might have made Moses even less confident that he could handle everything himself.

There is no transition between Moses’ second plea to Chovav (Numbers 10:31-32) and the announcement that the Israelites set out with guidance from the ark and the cloud (Numbers 10:33-34). The Torah does not tell us whether Chovav changes his mind and accompanies his son-in-law and the Israelites after all. I imagine he is torn between his duties as a father and a priest of Midian, and his deep affection for his son-in-law.

Yitro adopts Moses into his family when he is homeless. When Moses arrives at Mount Sinai with thousands of Israelites, his father-in-law comes, embraces him, and gives him good advice. When Moses leaves for Canaan, he begs his father-in-law to come with him.

Perhaps it is Moses who gives Yitro the name Chovav, “one who loves”. He has cherished his father-in-law’s love, and wants it to continue.

—

1 The Israelites and their fellow-travelers arrive at Mount Sinai in the third month after leaving Egypt (Exodus 19:1-2) and leave Mount Sinai for Canaan on the twentieth day of the second month of the second year after leaving Egypt (Numbers 10:11-12).

2 Rashi (11th-century rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), Ibn Ezra (12th-century rabbi Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra), and Ramban (13th-century rabbi Moses ben Nachman, a.k.a. Nachmanides), explained that Moses’ father-in-law was called Yitro until he decided to worship only the God of Israel4, and then his name was changed to Chovav—according to Ramban3, because he “loved” God’s teaching. Reueil was actually Yitro’s father, but Tzipporah and her sisters also called their grandfather “Father”.

A common modern theory is that the story of Moses’ marriage in Exodus 2:16-21 was written by the “J” source, someone from the southern kingdom of Judah, who thought of Moses’ father-in-law as Reueil. The other three stories in Exodus that include Moses’ father-in-law were written by the “E” source, someone from the northern kingdom of Israel, who thought of the man as Yitro. The redactor who compiled the book of Exodus from these two sources left in both names. (See Richard Elliott Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, HarperCollins, San Francisco, 2003.)

3 Exodus 4:18.

4 The classic commentators cite Exodus 18:11-12 as proof of Yitro’s “conversion”. I suspect that the Midianite priest was already familiar with the God of Israel, and may have pointed out Mount Sinai to Moses, since it was in Yitro’s territory.

5 Exodus 40:36-37.

6 Rashi is the acronym for 11th-century rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki.