The Israelites live in tents for 40 years, from the day they leave Egypt in the book of Exodus until they conquer Canaan in the book of Joshua. Only once, during the final year of their 40 years in the wilderness, do they own the land they are camping on: the east bank of the Jordan River.

King Sichon refused to let them pass through Cheshbon in last week’s Torah portion, Chukat, and the Israelites defeated his soldiers in battle, so now they own his land.1 The conquest of Canaan, across the river, is yet to come. But this new generation of Israelites is confident about killing or subjugating enough Canaanites to take their land, following God’s instructions.

Most of these nomads will become farmers in Canaan, with their own plots of land. This week’s Torah portion, Pinchas (Numbers 25:10-30:1), includes instructions on how to divide up Canaan. First God tells Moses and Elazar (Aaron’s son, the new high priest):

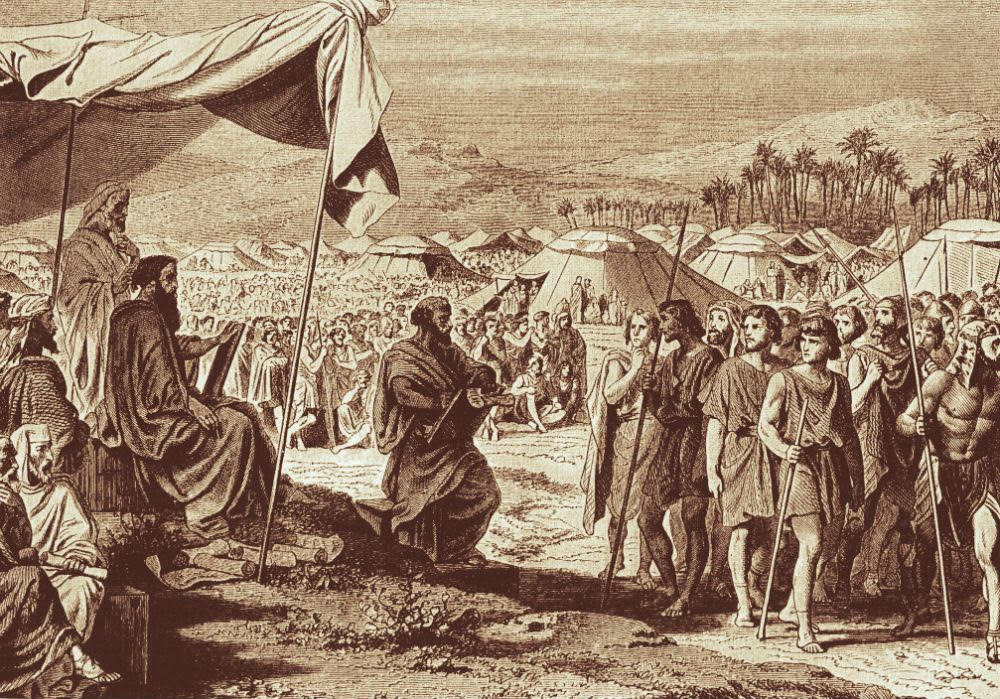

“Lift heads [take a census] of the whole Israelite community who is twenty years old and above, by the household of their fathers: everyone who goes to war for Israel.” (Numbers 26:2)

Moses and Elazar take a census, of all the men aged 20 and older except for the Levites, who do not go to war and will not be landowners. Following God’s instruction, they list the lineage of each man. Then God explains:

“To these you will allocate the land as a nachalah, according to the count of names. For the numerous [tribes and clans], you will multiply their nachalot, and for the few, you will reduce their nachalot; each will be given its nachalot according to its number.” (Numbers 26:53-54)

nachalah (נַחֲלָה) = hereditary possession, usually land. (Plural nachalot, נַחֲלֺת. From the verb nachal, נָחַל = take possession of land, inherit. From the same root as nachal, נַחַל = wadi, seasonal stream, stream bed, tunnel. According to S.R. Hirsch, nachalah means “property that ‘flows down’ like a stream from ancestors to descendants”.2)

In other words, after the Israelites conquer Canaan, the land will be allocated by tribe, and within each tribe by clan, and within some clans by branch, and within each clan or branch of a clan by the male head of household—adjusted according to population, so every household gets a parcel with the same value. The initial allocations will be made by a lottery. But from that point on, each parcel of land would be passed down through the same family.

In most countries today, land can be bequeathed to anyone the owner chooses. But in the Israelite kingdoms, land was automatically inherited according to a legal formula. If the landowner (usually male) had one son, all his land went to his son. If he had more than one son, the land was divided among them, with the firstborn son getting a double portion. Any daughters he had did not inherit land, and were dependent on their husbands, brothers, or sons. A wife of a deceased landowner became dependent on her sons; and if she had no sons, she was entitled to a levirate marriage with one of her husband’s brothers for the purpose of producing a son, who would then inherit the deceased man’s land.3 Otherwise, the land would revert to her deceased husband’s closest male relative.

The book of Proverbs indicates that a woman could earn income with her own business and buy land of her own.4 But she could not choose who inherited her land after she died. And every fifty years, all purchased land reverted to the families of the original owners.5

A new request from five daughters

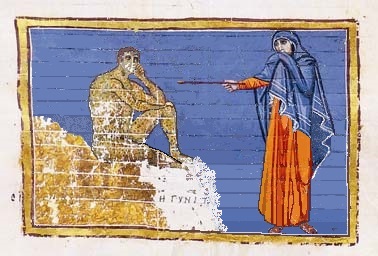

There seemed to be no way a woman could inherit land. Yet in the Torah portion Pinchas, right after the census of fighting men, five unmarried women boldly ask for their own nachalah in Canaan.

They came forward, the daughters of Tzelofechad, son of Cheifer son of Gilad son of Makhir son of Menasheh, of the clans of Menashe son of Joseph. And these were names of his [Tzelofechad’s] daughters: Machlah, Noah, and Chaglah, and Milkhah, and Tirtzah. (Numbers 27:1)

The lineage of their father matters, since the land that the Israelites expect to conquer will be divided by tribe, then clan, then branch, then household. Tzelofechad was a son of Cheifer in the Gilad branch of the clan of Makhir, which belonged to the tribe of Menasheh.

And they stationed themselves in front of Moses, and in front of Elazar the Priest, and in front of the chieftains and the whole community at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, saying: “Our father died in the wilderness, and he was not in the assembly that assembled against God in the assembly of Korach, for he died of his own guilt; and he did not have any sons.” (Numbers 27:2-3)

The five women are courageous, to come up to the Tent of Meeting and stand in front of all the men in Israel to make their claim. First they establish that their father’s heir (if he has one) has the right to an allotment of land:

- “He died in the wilderness.” Tzelofechad was one of the old generation who had to die while the Israelites waited 40 years in the wilderness for a second chance to invade Canaan. (See last week’s post, Chukat: Sapped.) The new census taken on the east bank of the Jordan lists all the men who are still alive—counted “by the household of their fathers” (Numbers 26:1). Here the five women point out that the land in Canaan will be distributed to the heirs of the men who left Egypt in the book of Exodus—and one of those men is their father.6

- “And he was not in … the assembly of Korach.” Two divine miracles killed all 250 men who rebelled against Moses and Aaron under the leadership of Korach, Datan, and Aviram. (See my post Korach: Quelling Rebellion, Part 1.) Tzelofechad’s daughters assert that their father was not in that faction—either because they think the descendants of those men do not qualify to inherit land in Canaan,7 or because they think Moses might be prejudiced against the men in that rebellion.8

- “He died of his own guilt.” This statement establishes that Tzelofechad never participated in any other group rebellion against God or God’s chosen leaders. He is only guilty of going along with all the Israelite men (except Caleb, Joshua, Moses, and Aaron) in refusing to cross the southern border of Canaan when they first arrive there from Mount Sinai.9

Therefore if Tzelofechad had had a son who was under 20 when the Israelites left Egypt, that son would be counted in the census now, and in the lottery for land after the conquest.

Next the five women make an argument they know will appeal to men:

“Why should the name of our father be subtracted from his family because he had no son?” (Numbers 27:4a)

Starting with Abraham in the book of Genesis, what men want the most is to have descendants who will remember their names.10

Only then do the daughters of Tzelofechad request a share of the land that will be allocated to the descendants of their grandfather Cheifer:

“Give us an achuzah among our father’s kinsmen!” (Numbers 27:4b)

achuzah (אֲחַ־ֻזָֽה) = holding, landed property. (From the root verb achaz, אַחַז = seize, hold fast.)

The five sisters do not challenge the rule of male inheritance. They ask only for the inheritable land that would have gone to their brother, if they had one. They are also careful to ask for land not for their own sake, but only in order to perpetuate their father’s name.

Their motivation

What motivates the five sisters to make their novel request to inherit land? Here are some possibilities proposed in commentary from the 3rd century C.E. to the 19th century:

- They love the land of Canaan like their ancestor Joseph, whose deathbed wish was to be reburied there (Rashi, 11th century).11 I believe that although these women might love the idea of the “promised land”, they cannot love the actual land; unlike Joseph, they have never been there. At most, they can see the other bank of the Jordan, which looks no different from the side where they are camped.

- They love their father and actually do want his name to be remembered, in the lineage of inherited land as well as in the lineage of any sons they might have someday. If they did not get Tzelafechad’s nachalah, their future sons would be listed by the names of their fathers, rather than by the name of their maternal grandfather (Hirsch, 19th century).12

- They do not want to be adopted into their uncles’ households; they want to continue to run their own household, even though none of them has a son to be the titular head of their family. Although earlier commentary does not mention this possibility, it does point out that the five women are united, speaking as one (Sifrei Bemidbar, 3rd century CE).13

- They are proto-feminists who believe that God, unlike human men, wants to distribute good things equally (Sifrei Bemidbar, 3rd century CE).14

The divine answer

After the daughters of Tzelofechad make their argument, Moses checks with God, who replies:

“Rightly the daughters of Tzelofechad speak; you shall certainly give them an achuzah of a nachalah amidst the brothers of their father, and you shall make the nachalah of their father pass over to them. And you shall speak to the children of Israel, saying: “If a man dies and has no son, then you shall make his nachalah pass over to his daughters.” (Numbers 27:7-8)

This ruling promotes women from chattels to second-class citizens who can inherit land—but only if their father dies without sons. In the Torah, God never praises independence, but does praise compassion for the unfortunate. A woman without a father, husband, brother, or son to support her is considered unfortunate.

A side-effect of the new law is that a daughter who inherits and remains unmarried would have financial independence that no other women possess.

But the male relatives of the daughters of Tzelofechad assume that all women want to marry and have sons. In next week’s double Torah portion, they come back to Moses to protest against God’s new inheritance law. (See next week’s post: Masey: Tribal Loyalty, Part 2.)

The daughters of Tzelafechad succeed because they are united, delivering a single clear request without distractions; because they give a reason that appeals to the men’s customary way of thinking; and because they limit their request so it will not disenfranchise any sons of landowners. Their first success is in persuading Moses that it is worth checking with God. Their second success is that God’s answer grants their request—and generalizes it to all cases in which a man dies without a son.

The only men’s issue that the women do not address is tribal loyalty. In next week’s Torah portion Masey, their male cousins complain because they do not want any of the land assigned to their tribe to be inherited by a different tribe—which would happen under current law if any of the daughters of Tzelafechad married a man from another tribe. (Under the current law, a son is counted as a member of his father’s tribe and clan, not his mother’s. So if any of Tzelafechad’s daughters had a son with a man from another tribe, her land would become a nachalah of her son’s tribe, not of the tribe of Menasheh.)

The women act out of loyalty, too. But their loyalty is to their immediate family: to each other, and perhaps to their father’s memory.

When we write wills today, we determine our inheritors—who will then dispose of our property according to their own wishes after we die. There is no nachalah except for the royals and nobles in some countries.

Yet I remember growing up next door to the Pratts, who had four daughters and kept “trying” until they had a son. Their youngest daughter, who was in grade school with me, told me that her parents wanted a son “to carry on the family name”. Even when land was not an issue, the men of our parents’ generation and our own felt sad when they had no son to perpetuate their last name, and all the family history that went with it.

I wonder about the next generation.

- Numbers 21:21-32.

- 19th-century Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Bemidbar, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2007, p. 554.

- See Deuteronomy 25:5-10; Ruth 1:11-13, 3:9-13, 4:1-12; and my post on Genesis 38:6-26: Vayeishev & Mikeitz: Identity Crisis

- Proverbs 31:16 says a superlative wife not only runs a successful business out of her home, but “she sets her mind on a field and she takes it”.

- The yoveil or “Jubilee” year described in Leviticus 25:8-28.

- A point considered at length by 18th-century Rabbi Chayim ibn Attar in Or Hachayim.

- Talmud Bavli, Bava Batra 118b.

- Ramban (13th-century Rabbi Moses ben Nachman).

- Numbers 13:25-14:35.

- Genesis 15:1-6.

- “Just as Joseph held the Promised Land dear, as it is said, (Genesis 50:25) ‘And ye shall bring my bones up (to Palestine) from hence’, so, too, his daughters held the Land dear, as it is said, (v. 4) ‘Give us an inheritance’.” Rashi (Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki) on Numbers 27:1, translation by www.sefaria.org.

- “As for Tzelafchad, however, the family name will come to an end already in the second generation, and the extraordinary opportunity for its perpetuation presented by the apportionment of the Land according to families and houses will be lost, and his name will cease to be remembered.” Hirsch, ibid., p. 551.

- “When the daughters of Tzelofchad heard that the land was to be apportioned to the tribes and not to females, they gathered together to take counsel.” Sifrei Bamidbar 133:1, translation by www.sefaria.org.

- “The mercies of flesh and blood are greater for males than for females. Not so the mercies of He who spoke and brought the world into being. His mercies are for males and females (equally). His mercies are for all! As it is written (Psalms 145:9) “The L-rd is good to all, and His mercies are upon all of His creations.” Sifrei Bamidbar 133:1, translation by www.sefaria.org.